THE MONK OF SOUND: JEAN-CLAUDE ELOY

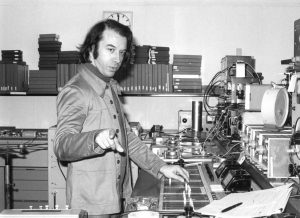

Born in Mont-Saint-Aignan (France) in 1938, Jean-Claude Eloy completed his musical studies at the Paris Conservatory, where his teachers include prestigious names such as Darius Milhaud and Maurice Martenot. While still a boy, he is an excellent pianist. He plays Bach, the classics, romantic music, his beloved Debussy. Outside the academic field, he has clandestine interests in the newest music of his time: Webern, Messiaen, the serial music. The young Eloy does not only cultivate musical interests. He reads a lot, especially surrealist poetry, Paul Eluard, André Breton, Henri Michaux. Another passion is the cinema, which will influence him not a little in his compositional work, as evidenced by the long essay Je suis un enfant de l ‘âge du cinema, written in 2010.

While still a teenager he became passionate about the traditional musics of the world, he listens to the Japanese gagaku, the Indian dhrupad, the Indonesian gamelan, classical music from Iran, the liturgical chant of the monks of Tibet … These amorous and assiduous listening shapes his acoustic sensitivity and will result fundamental for its evolution. Far from any exoticism, Eloy develops the Stockhausenian idea of Weltmusik (“world music”) in an entirely original way, aspiring to a hybrid, transcultural music, to a music that arises from the fusion and mutual transformation of different cultures, from their “intermodulation”.

In the 1960s Eloy was among the most promising pupils and protégés of Pierre Boulez, from whom he later distanced himself firmly. The years spent in the United States (1966-1970), first as a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, then as a wanderer in the American deserts, are rich in experience, helping him to free himself from the aesthetic dogmas in European musical milieus and so to find his true voice. His return to France in 1970 marks a new beginning, Eloy is determined to follow his path with radicalism and without accepting compromises. The turning point is Kâmakalâ (“The triangle of energies”), a work for three orchestras and five choirs, in which the references to traditional Asian music are henceforth completely evident. After the performance of Kâmakalâ, this work of tantric inspiration that was to mark a point of no return in his path, in 1972 – thanks to the mediation of Karlheinz Stockhausen, dear teacher and friend of him – Eloy receives a commission from the WDR of Cologne. Thus, his long-cherished dream came true: finally he was able to work in an electronic music studio. It’s there that he composed Shânti.

After having clearly detached himself from his teacher Pierre Boulez, from the beginning of the 1970s Eloy took a radical path composing a series of impressive sound frescoes which are characterized by the surrealistic fantasy, the meditative character, the acoustic intensity, and not least by the long duration of performance.

Eloyʼs music is today somehow “outmoded” and at the same time profoundly necessary. It can be an antidote. In an era of global acceleration and shortness of breath, Eloy dares to compose long or even very long works (up to 4-5 hours without interruption), sound journeys with an epic breath, preferring meditative temporal dimensions; in an almost completely desacralized world. he proposes a contact with the sacred and invites us to contemplation; in a society dominated by the visual, he emphasizes the importance of concentrated listening.

Eloyʼs music is among the most intense of our time. It has a transformative power, it can lead very far. After an Eloy concert, the listener is no longer the same person. All one needs is commitment of mind, dedication to the sounds, abandonment to the flow.

Leopoldo Siano

Some thoughts towards the listening of Shânti by Jean-Claude Eloy

In Sanskrit “shânti“ means “peace“. However, Eloyʼs Shânti is not a “pacifistic“ work. Paradoxically, despite the title, it is also a work on war as a cosmic principle. The “war“ is here to be understood in the sense of Heraclitus, Eloyʼs favorite Greek philosopher. The pólemos as the father of all things, the struggle between opposites. Nothing can exist without its contrary. From the contradiction and the contrast, movement is generated.

War is everywhere, always: there are microscopic wars within the body, fights between animals, religious battles, social, economic, artistic competitions; there are quarrels among families (or among relatives), struggles with oneself, or even catastrophic events in nature, telluric and astral. Precisely because we are always in the midst of a continuous struggle and inevitable suffering, organized wars must be categorically avoided. For Arthur Schopenhauer the Will to Life is a struggle for satisfaction, but doing that it tears itself apart. The intrinsic violence of the cosmic event of creation is of infinite power. For some, war can certainly be a Dionysian, intoxicating event that the unconscious is surreptitiously seeking. However, the “unproductive dissipation” can be fully experienced in another way, especially through art understood as the supreme activity of the spirit. The madness of artists, unlike that of politicians, is salvific. Hermann Nitsch once said: “If there were no wars, man would have to stage them in the theater“. The destructive forces, which are undeniably an integral part of the man, of the cosmos, must be elaborated through art, precisely to avoid wars.

All repressed (Dionysian) energies, sooner or later, turn into aggression, fear, neurosis. By becoming aware of them, of the shadows of one’s psyche, integrating them, one can try to channel these forces for creative purposes. And it is here that one needs a straightening, a counter-poison: ART – a tool for intensifying life, the sense of being, here and now. An art that heals, therefore. Without creativity, the world works very miserably. The true capital of the human being is creativity, said Joseph Beuys. The lack of true knowledge – that of oneself and, thus, of the world – seems to be at the root of global dysfunctions. Without first transforming oneself, without experiencing oneself with intensity, one cannot have the ambition to change the world around us. Creativity is the most decisive “weapon” to combat ignorance, greed and violence; the supreme tool to channel, in a healthy way, the cosmic energies that – volens nolens – flow through us.

One may wonder what the task of art is during wartime.This question is rather otiose since the mission of art during a war is the same as in peacetime. At stake here is the very conception of art and the way to experience it. If art is a ritual, it means that as such, it must always be performed to ensure the bond of an individual with the anima mundi: an instrument must be continuously tuned. It is fundamental to understand art for what it is, not as decoration, pleasant divertissement or bourgeois pastime, but as a ritual, as magic, as a means for knowledge, as a work on oneself and consequently on the outside world. “All art is quite useless”, says Oscar Wilde. In fact, art – like meditation and prayer – is (apparently) useless. But there is a “limit of the useful“ (Georges Bataille). Matter, money itself, if understood differently, are spiritual.

Shiva, an Indian god to whom Eloy feels very close, is a creator and destroyer at the same time. The Shânti sound fresco tells us not only about human wars but also about universal catastrophes. At the end of the work, to be sonically evoked, is the pralaya of the Indian tradition, the conflagration at the end of a cosmic era. All conflicts dissolve, the entire universe is reabsorbed, to be then reborn. Modern descriptions of possible atomic warfare are nearly identical to those found in ancient Indian texts such as the Puranas, notes Alain Daniélou[1], an author that Eloy loved much.

The subtitle of Shânti is: “meditation music”. Many of Eloyʼs mature works undoubtedly lead to meditative experiences – after all, one can fully experience this music if one listens to it lying down (which the composer himself recommends for his concerts) to ease psychophysical tensions and abandon oneself to the sound flow of images, memories and visions, to become more open and receptive. Certain sounds used in Shânti, as in other compositions by Eloy, favor a contemplative state in the listener, a “tantric” purification of the mind, an absence of thoughts; we are speaking in particular of those dense sound blocks defined by Eloy as “meditation sounds”. But Shânti certainly has nothing to do with the commercial products of the so-called “New Age” or with the “relaxation music” to play in the background. Shânti is not functional music but a work of art. “Meditation“ is here to be understood as the “composer’s meditation“ which the listener has to follow with extreme attention. The sound that Eloy has constantly sought is comparable to a “meditating flame”. Not only “music to meditate” therefore; in this music it is the sound itself that meditates.

November 2022

Leopoldo Siano & Shushan Hyusnunts

[1] La Fantaisie des dieux et l’Aventure humaine. Nature et Destin du Monde dans la Tradition shivaïte, Le Rocher: Monaco 1985.